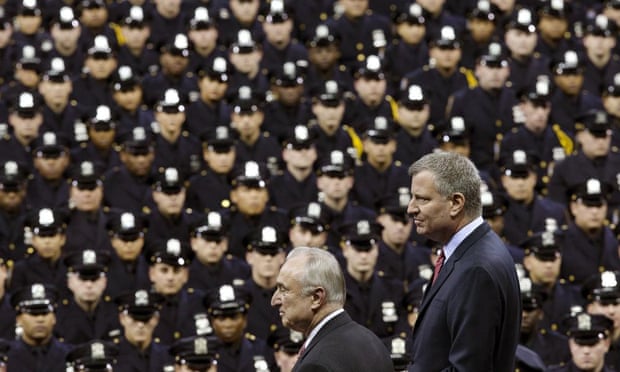

Hiring more non-white officers is difficult because so many would-be recruits have criminal records, the New York police commissioner, Bill Bratton, has said.

"We have a significant population gap among African American males because so many of them have spent time in jail and, as such, we can't hire them," Bratton said in an interview with the Guardian.

Police departments, responding to widespread protests against several high-profile police killings of black men, are boosting efforts to recruit more non-white officers. But budget restrictions, strained relations between police and minority communities and, according to Bratton, a history of indiscriminate policing tactics that disproportionately target black and Latino men complicate the department's goal of racial parity.

Bratton blamed the "unfortunate consequences" of an explosion in "stop, question and frisk" incidents that caught many young men of color in the net by resulting in them being given a summons for a minor misdemeanor. As a result, Bratton said, the "population pool [of eligible non-white officers] is much smaller than it might ordinarily have been".

The application process to join the NYPD includes, among other things, a complete criminal background check.

Convicted felons are automatically disqualified from the NYPD applicant pool, as well as anyone guilty of a domestic violence charge or who has been dishonorably discharged from the military.

Summonses, however, do not automatically disqualify a candidate, though they are taken into account during the application process. For example, a summons for disorderly conduct would not preclude a candidate from being accepted into the force, but repeated convictions for an offense that demonstrates "disrespect for the law" could result in disqualification.

The controversial stop-and-frisk policy was struck down in 2013 by a federal judge, who called the practice a "policy of indirect racial profiling". Judge Shira A Scheindlin found that the program led officers to routinely stop "blacks and Hispanics who would not have been stopped if they were white".

But critics say Bratton - who helped shrink the widespread use of stop-and-frisk -is partly, if not ultimately, responsible for the relative paucity of eligible non-white recruits.

"It is a net that he set out for them," said Rochelle Bilal, vice-chair of the National Black Police Association and a former Philadelphia police officer. "If [Bratton] didn't stop people for nothing, he might have a bigger pool to hire from."

Despite his repudiation of stop-and-frisk, Bratton still believes broken windows policing – a crime-fighting strategy of enforcing low-level crimes to stop offenders from committing more serious ones in the future – is indispensable to keeping the city safe.

"We will continue our focus on crime and disorder," Bratton told the Guardian in an interview on May 20, for a wide-ranging, two-part feature on the NYPD. "I make no apologies for doing that."

Critics say the policy he champions disproportionately affects poor, urban communities and leads to the mass incarceration of young black and Latino men for relatively minor offenses.

"Stop-and-frisk was not the heart of the problem," said Robert Gangi, the director of the New York City-based Police Reform Organizing Project (Prop), which advocates for an end to Bratton's broken windows policy. "Stop-and-frisk was the symptom of blatantly racist policing, known as broken windows."

Serving as the head of the NYPD in the early 1990s, Bratton was one of the first commissioners of a major US city to adopt the broken windows policy. Under his watch, crime rates plummeted.

Bratton then took it with him to Los Angeles, where he was the head of the department from 2002 until 2009. During his tenure, low-level arrests increased, as did stops of pedestrians and motorists from 587,200 in 2002 to 875,204 in 2008.

When Bratton returned to the NYPD in 2014, he immediately dropped the city's defense of the stop and frisk policy, a campaign promise of his boss, New York mayor Bill de Blasio. But he kept broken windows, even as critics say the policing model has no proven connection to New York's dramatic decline in major crime.

The program has come under renewed scrutiny after Eric Garner, a Staten Island man, died during an encounter with NYPD officers while being taken into custody on suspicion of selling untaxed cigarettes.

Ensnaring young people – often black and Latino men – in the criminal justice system for seemingly innocuous crimes is not a winning strategy for attracting officers of color to the police force, Gangi said.

"We're certain the disfavor and the antagonism in the black community toward the police is a principal factor in why so few black men want to become police officers," he said.

Departments have been making gradual progress in reducing racial disparity in the force. An analysis by the Associated Press following the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teen in Ferguson, Missouri, found that racial diversity was improving, with the gap between black police officers and the communities where they serve narrowing over the last few decades.

The analysis, based on census data and 2007 federal figures, found that 23% of New York's population is black compared with 16% of the NYPD.

The city last year announced that police officers would stop arresting people in possession of small amounts of marijuana, which Bratton said he welcomed as it would divert more resources to reducing violent crime. The move was expected to curb tens of thousands of low-level arrests for pot possession, which the mayor said affected young people's chances of getting a job, good housing or even a student loan.

Delores Jones-Brown, a former New Jersey prosecutor and a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said non-white defendants were convicted at disproportionate rates compared with their white defendants in large part because arrest rates were disproportionate.

"You can't get arrested unless the police are paying attention to you," she said. "And the police are paying attention in communities of color more so than they are in communities that are more affluent or more suburban."

Black defendants were 15% more likely than white defendants to be imprisoned for misdemeanor offenses and drug offenses, and 14% more likely than their white counterparts to be imprisoned for felony drug offenses, according to a July 2014 study, published by the Vera Institute of Justice of prosecutions handled by the Manhattan district attorney's office.

Overall, black defendants were 5% more likely to be sentenced to time in prison than white defendants facing a similar charge, the study found.

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service - if this is your content and you're reading it on someone else's site, please read the FAQ at http://ift.tt/jcXqJW.

http://ift.tt/1GwwEkV NYPD chief Bratton says hiring black officers is difficult: 'So many have spent time in jail' via top scoring links : news http://ift.tt/1FPhEIj

Put the internet to work for you.

No comments:

Post a Comment